One hundred miles.

You’ll commonly hear cyclists asking each other whether they’ve ever

ridden “a century”, a lofty goal similar to that of completing a marathon for runners. Yes, some people are

able to ride further, but for most, once they’ve gotten to 100 there’s no need to

prove themselves further, except perhaps to go find another century to do

that’s more epic in one way or another.

Once my wife Beth and I realized in the early 2000s that our

40+ -year old knees, hips, and other moving body parts were not going to

withstand decades of additional long-distance running, we started looking for

another way to punish ourselves. We

discovered cycling, and before long both of us were able to complete a 100-mile

ride. We then started searching for

challenging rides and events to do around the country, frequently involving rides of 100 miles or more, many of which are depicted below:

Bike Tour of Colorado, Vail Pass - 2011

John with Daughter Anna, Whiteface Mountain Summit, New York - 2012

Blue Ridge Parkway, Smoky Mountains, North Carolina - 2014

PAC Tour Alaska, 1200 miles in 10 days, Valdez, AK - 2007

Thread City Cyclers RAGRBRAI Team - Iowa, 2009

Thread City Cyclers RAGRBRAI Team - Iowa, 2009

PAC Tour Winter Camp, Bisbee, Arizona - 2016

Natchez Trace Parkway, Alabama, 2016

Boulder City, Nevada - 2017

One of our adventures took us to Virginia in 2012, where

there was a six-day ride with a longest day of 80 miles. Beth pointed out that if we just logged 20 miles

before everyone else woke up that we could end the day with 100. “Furthermore”, she said, “wouldn’t it be neat

if we were able to do a 100-mile ride in every State?”. Although initially skeptical, John

ultimately embraced the idea when he realized that this would give him

something to talk about at dinner parties for many years to come. We rode 100 miles that day, bringing our

total to 10 States, and then over the next seven years added another 23, to

bring the total at the beginning of the 2019 riding season to 33

With Friends Bill and Phil, Tennessee - 2014

With Friends Hart and Liz - Salado, TX - 2017

Beth and Friend Bill, Gaffney, Georgia - 2014

Zion National Park - Utah, 2017

PAC Tour, Wisconsin - 2013

Natchez Trace Sag Wagon Driven by John's 81-year Old Mom Jean - Alabama, 2016

Natchez Trace Parkway, Mississippi - 2016

Beth with Friends Phil and Bill in a Sad Town on a Hot Day in Arkansas - 2016

Beth with Friends Jim and Sylvia - Cycle Oregon, 2018

As we checked off the states within a day’s driving distance

of our home base in Connecticut, the pace of our quest has slowed, and in many

years we’ve only been able to add one or two new states to the tally. We realized that with our 60th

birthdays approaching that we’d best get on our horses and get this thing done

or we’d be doing it in wheelchairs. It

was Beth who first suggested the possibility of a whirlwind road trip to grab

the balance of the states in one fell swoop, minus Hawaii due to certain

logistical challenges. I was freshly

retired from a 35-year career and I was looking

for a project, so I embraced this mission with more than a small amount of

gusto. I pulled out the Rand McNally Road

Atlas and started to develop an itinerary that would take us through the 17 remaining

states in the contiguous U.S. in as efficient a manner as possible. Over the course of several months I

researched potential rides, sought lodging with friends we have scattered

across the country, and acquired the pile of stuff we’d need to support

ourselves along the way. This would not

be a self-supported fully-loaded cross-country bike tour in the classic

sense. Instead, we’d pile our bikes and

our mountain of gear into our Dodge Caravan and use the vehicle to hop-scotch across the country to each successive state where a ride was required.

After plotting a route on the map and thinking about

logistics, we realized it would take about seven weeks to complete our task. Our selection of a departure date in mid-May

would be early enough to beat the worst of the summer heat, late enough to

allow the plowing crews to clear the last of the winter’s snows from the high

passes in the Rockies, and at the right time of year to get maximum daylight

for early starts.

On the morning of May 18th we turned the keys to

the house over to a house-sitter, said good-bye to our dog and two cats, called

our moms to tell them we loved them, and pointed the van toward Ohio for our first

test. We had three bikes stowed

comfortably inside – Beth’s Trek Silque, my Cannondale Synapse, and our brand

spanking new Co-Motion Carrera Tandem, painted in “Lusty Red” for maximum speed.

For extra carrying capacity we purchased the largest Yakima roof-top carrier available,

and our loaded rig bore a distinct resemblance to the space shuttle flying back

to Cape Canaveral on the top of a 747.

Our camping equipment went in the cartop carrier. The rest of the stuff rode inside with us,

stacked nearly to the ceiling.

Along the way I endeavored to write a log of our adventures

to share with friends. I’ve included

that log as originally written and have embellished it with some photos we

snapped along the way.

Getting there can be Half the Battle

Prior to the trip I had brought our 2013 Dodge Caravan to

the dealer to have them do a “free 23-point safety inspection”. “Everything’s running great”, I said, “so you

probably won’t find anything”. They

called me a few hours later to say that I needed to replace my struts, various

components of the braking system, and several mysterious mechanical items that

I suspected they had simply made up.

After paying the $2500 bill I was assured that we’d be good to go on our

8000-mile voyage. On the way back from

the dealer I discovered that the air conditioning was out, so I did a U-turn

and brought the car back. “We’ll look at

it right away”, they said, “probably just needs the refrigeration liquid

refreshed”. Later that day I was told we

needed a new condenser for $1,000. A

little while after that they called again to let me know that the cost would be

twice that quoted because various metal parts had seized onto other various

metal parts and the only way to remedy the situation was to start cutting

things up and throwing them away. I

returned to the dealer the next day and gave them some more of my retirement

funds. With our van now worth $5,000

more than it had been three days earlier, we were confident that nothing else

could go wrong.

Halfway to Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania on our first day of

driving the warning lights for the ABS brake system came on as well as a little

squiggly symbol of unknown importance. A

little while later the little engine warning light came on, and a while after

that the cruise control stopped working, which saddened my right foot. I chose to ignore all of these symptoms since

the vehicle was continuing down the road under its own power and the various

issues were not inconveniencing us.

Unbeknownst to us, the Gods that govern all things mechanical had one

more trick up their sleeves. As we went

to close the rear hatch of the van after our first night of camping, the

automatic door latching mechanism got in its head that it would like to unlatch

the rear door every time it was closed, which meant an unlocked unlatched rear

door that would open randomly going down the road for the rest of the

trip. Not good. After a few dozen attempts we were

able to get the door closed but we were then so afraid to open it that we

stopped using the door and for the rest of the trip and accessed our three bikes

and our gear through the side doors.

Weeks 1 and 2 – Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kansas,

Nebraska

We had a busy start to our bike adventure and only after two weeks on the road did feel like I had the time, energy, and

backlog of amusing anecdotes to provide the first chapter of our

experience.

I’ll get the statistics out of the way first in order to

satisfy those who would like to skip the stories of mishaps, misery, and malfeasance.

Start Point

|

Date

(2019)

|

Riding

Distance (miles)

|

Elevation

Gain (ft)

|

Average

Speed (mph)

|

Max

Speed (mph)

|

High

Temp

|

State

Century

|

Xenia, Ohio

|

5/20

|

101

|

807

|

15.3

|

24.8

|

70

|

#34

|

Tell City, Indiana

|

5/22

|

103

|

6096

|

14.2

|

46.7

|

75

|

#35

|

Golconda, Illinois

|

5/24

|

102

|

8110

|

12.9

|

46.0

|

91

|

#36

|

Poplar Bluffs, Missouri

|

5/26

|

108

|

4626

|

15.5

|

40.9

|

85

|

#37

|

Beatrice, Nebraska

|

5/28

|

102

|

2614

|

16.5 (tandem)

|

35.6

|

68

|

#38

|

Kansas (starting in Odell, NE)

|

5/29

|

100

|

3566

|

15.0 (tandem)

|

33.7

|

75

|

#39

|

Xenia, Ohio – A Rail

Trail Crossroad

As a preliminary planning tool for our trip I had researched

the Rail-to-Trail Conservancy’s “Hall of Fame” list of 25 great rail trails in

the U.S. One of those trails was paved

and happened to be in Ohio, where we had not yet ridden a century. The Little Miami Trail runs for 90+ miles

north of Cincinnati. It connects to a

myriad of other trails providing one of the best networks of improved rail trails

in the country. Ground zero of that

trail network is Xenia, Ohio, the intersection of rail trails that radiate out

in five different directions.

Xenia Ohio - A Rail-Trail Crossroad

We stayed in Xenia in an AirBNB that Beth and found for a

remarkable and somewhat frightening $38 per night. We had our choice of rooms and chose the room

in the basement, perhaps with the unconscious recollection of the F5 Tornado

that wiped out much of the town and killed a bunch of people in 1994. The downside to the room, which we thought of

while we were trying to go to sleep, was that the only exit was via a steep set

of wooden stairs. That’s not really a

down side unless the house is on fire or has been crushed by a tornado, in

which case it could be a major downside.

We woke the next morning without the need for an emergency

exit, and pointed our bikes south for a 50 miles run toward our turn-around point in

Milford. The towns along the way clearly

have a love affair with the trail. It

gets heavy use, and we saw smiling cyclists and walkers for the entire

distance, although not so many that it impeded our progress. An overnight thunderstorm had deposited

hundreds of sticks and downed one large tree across the trail which we had to

navigate through on our way south. By

the time we returned north a few hours later the tree had been removed and

virtually all the sticks had been kicked to the side. The towns the trail passes through cater to

cyclists, especially the town of Loveland, which has a bustling downtown with a

well-stocked bike store and several great lunch spots. We were off to a good start.

With the Cincinnati Reds Dude on the Little Miami Trail, Ohio

Indiana Wants Me (or

so says the song)

Nothing says boring to a cyclist like Indiana. OK, not quite nothing - Illinois, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma give

Indiana a good run for its money in the boring category. A major planning tool for this trip was the

Rand McNally road atlas. When I got to

planning the routes for Indiana and Illinois, I consulted the atlas and found

that the only geographically redeeming features of these states lay in the far

south just north of the Ohio River, where the geography resembled that of

northern Kentucky. Indiana has Hoosier

National Forest and Illinois has the Hiawatha National Forest. We found routes that took advantage of each

of these sparsely populated areas and quickly discovered that National Forests

tend to be located where farming is poor – in the HILLS.

The Rand McNally road atlas can only tell you so much – it shows

you the State highways and some of the county highways but none of the back

roads. It generally does not tell you

how wide the shoulder is, how steep the hills are, how heavy the traffic is, or

whether there are rumble strips in exactly the place you want to ride. It also does not tell you whether the road is

closed due to bridge construction or whether the road is flooded due to all the

rain they’ve gotten in the Midwest this spring.

For all these reasons and because we didn’t have anything better to do

in our off days, we drove certain portions of our routes before riding

them. This practice proved to be

extremely valuable in Indiana. During

our drive along the portion of the route that parallels the Ohio River we came

to a sign that said – Road Closed, 4 miles ahead. The detour for this closure would have taken

us far out of our way on the bikes, so we drove to the construction area to

find a bridge under construction. We

spoke to the DOT supervisor at the site (Bridget) who told us that if we

returned the following day that they’d let us walk our bikes through the bridge

site to the other side and save ourselves a 20-mile detour.

The Preliminary Plan for the Indiana Ride (later amended)

It’s always a challenge finding a safe place to park a car

laden with the valuable trappings of life on the road for 8 weeks. While sometimes we rode from a hotel or

campground, at other times, such as Indiana, we had a remote start that we

needed to drive to. We parked the car in

front of the county courthouse in Tell City, Indiana under the watchful eye of

a bunch of security cameras. Doesn’t get

much better than that.

Iconic Indiana Image

Our Indiana route headed north, directly away from the Ohio

River (and the Kentucky border), into the hills. We’d found a County Highway that passed

through the Hoosier National Forest and kept us off the busy State

Highway. The road was scenic and lightly

traveled, but had lots of ups and downs along the way, with speeds on many of

the downhills topping 40 mph. We got a

picture of Beth in front of the Southern Indiana Squirrel Hunters

headquarters. Beth has an aversion to

squirrels and embraces the association’s attempts to eradicate that species

from the planet. About 25 miles into our

route we looked west at the darkening skies and realized we were in for a wet

time (which we later got). A slight

detour got us back to our campsite where we were able to pick up

raincoats. We continued through the hill

country and stopped for a peanut butter sandwich in the Town of English,

Indiana. Quaint sounding name but sad

little town, with about two-thirds of the buildings in an advanced state of

decay and almost all of the businesses shuttered. The one surviving business appeared to be a

golf course. The return to Tell City was along the Ohio River with views of

Kentucky on the far shore – a flat ride punctuated by a 10 minute walk through

a very sketchy bridge construction site.

Alternative Recreational Opportunities in Indiana

Beth Enjoying a Bridge Out Adventure in Indiana

We left Indiana with our one probing question unanswered –

What the heck is a Hoosier?

Illinois – it’s not

all flat

As much as I tried to program our ride routes and schedule

for this trip, we’ve quickly discovered that it’s critical to be flexible and

open to modifications to the plan. In

consultation with the Rand McNally Road atlas, I’d planned a route that

included a State Highway north of a town curiously named “Cave in Rock” for a

spectacular cavern opening in the limestone at the shore of the Ohio

River. When we drove the route the day

before, we realized that the road I’d chosen was blessed with constant heavy

truck traffic hauling limestone out of a nearby quarry. Not safe.

Not fun. We agreed to stop in

Cave in Rock at a diner to re-assess.

The place mat for the diner happened to be a county map that depicted

all of the local roads, with a specific indication of what was dirt (most of

the roads) and what was paved (few of the roads). We scrapped the original route, and right

there on the spot designed a completely new route by using a highlighter to mark

good riding roads on the place mat and then finding a way to connect them.

Cave-in-Rock, Illinois (on the Ohio River at the border with Kentucky)

We stayed the night before our Illinois ride in a motel in

Galconda, IL on the Ohio River across from Kentucky. The weather on our Illinois ride day was

projected to be sunny and humid with temperatures in the 90s, so we rolled out

early enjoying the 5:30 AM sunrise. We

quickly completed a leg along the Ohio River and then turned inland and into

the bigger hills. This was a hard day –

the hills came at us one after another with few breaks. The roads of the Hiawatha National Forest

were beautiful but almost our whole time was spent climbing at four or five

miles per hour, with the only breaks being the downhills that at 40-plus

mph were over far too quickly. One break

to the climbing was provided by a six-mile detour we took to the Garden of the Gods, a spectacular sandstone cliff formation typical of

what you’d normally expect to see in the southwest.

Garden of the Gods, Illinois

Southern Illinois - Nothing but Hills

From about the halfway mark of the ride it was super-hot and

finding water was a challenge. On one

long featureless stretch at the 60-mile turnaround point we found a

casino/bar/convenience store that was strategically located exactly where we

needed it to be, beyond the limits of a town that did not allow alcohol or

gambling. While our use of alcohol and our

gambling losses at this establishment were limited, we did enjoy the air

conditioning and their ice-cold drinks before heading back into the blast

furnace that would be our life for the next five hours or so. We hit several memorable hills on the way

back to the car, including a steep 600-footer called Williams Hill that will

reside in our memories for some time.

This was a tough day – at 8100 vertical feet and 91 degrees this ultimately

turned out to be our toughest day of the trip – in ILLINOIS ! Adding insult to

injury, in cleaning Beth’s bike after the ride, we discovered her pedal had

seized up, requiring massive strength to force the required rotation (editor’s

note – Beth wrote the part about massive strength).

Missouri – The Show

Me State

Show me what? I can’t

stop having inappropriate thoughts every time a Missouri “Show Me State”

license plate drives by. I’ll try to be

more mature in the future.

Beth and I have not been planning too far ahead. We know the direction we’re going and the

states we need to hit in what order, but the exact routes, the exact schedule,

and even the towns we stay in have been flexible and have been becoming more so

as we continue our journey. This flexibility

was fully required a few days back when we decided to find a campsite in

Missouri for the second Saturday and Sunday nights of our trip. Surprisingly (at least to us), lots of people

like to camp over the Memorial Day weekend.

Our last-minute research determined that there was not a campsite

available on those two days anywhere north of the Mexican border, so we

returned to the Air BNB app, failed there, and then moved on to hotels.com

where we located a Motel 6 in Poplar Bluffs, Missouri at the edge of

the Ozark Mountains in the extreme southeast part of the State.

Riding Along the Edge of the Ozarks, near Poplar Bluffs, Missouri

We arrived in Poplar Bluffs about 14 hours before our next

scheduled ride but because this was an unplanned overnight spot, we had no

specific ride planned. We stopped at the

local bike shop where the owner was more than happy to do what bike shop owners

do best, talk to us about biking. The

challenge was to find a ride that was not too hilly (as the Ozarks are known to

be) but not too boring (as the dead flat area south of Poplar Bluffs is known

to be). The owner helped us map a route

that was a combination ride that would start in the hills and finish in the

flats. Because the route was a bit

confusing, we elected to drive the entire 100-mile course before we rode

it, steering the van through beautiful rolling

country roads with creative names like “Highway PP” and “Highway K”. On the drive back into town we discovered

that one of our key connections would have sent us down an 8-mile gravel road, an unacceptable option to both of us with our skinny tires. We retreated back to our hotel and identified

a paved alternative back into town that would keep us happy, or so we thought.

Ride day in Missouri was clear and cool and we started into

the hills in good spirits, enjoying every moment. At our halfway point in

Doniphan, Missouri a miracle happened when Beth agreed to stop with me at the

Sonic Burger drive-in for lunch. Back on

the road after our junk food fix, we faced a 45-mile ride back to our hotel,

with most of it through dead flat wide open plowed fields. We picked up a fortuitous tailwind and were

able to make over 40 miles in under two hours on the return, our fastest riding

so far on the trip.

At the 102-mile mark, now on the re-routed section we had

planned back in the hotel room, we encountered a “Road Closed - Bridge Under

Construction” sign. Emboldened by our

successful bridge crossing in Indiana a few days earlier, we proceeded into the

construction zone which was unattended on a Sunday. We walked our bikes past cranes, payloaders

and a myriad of other construction equipment to the top of a new overpass that would eventually cross two busy railroad tracks. They

had not yet put the new bridge in place, so we faced the choice of backtracking

and taking our chances on an alternative route (Beth’s preferred option) or

scampering down the steep gravel incline, crossing a couple of muddy ditches,

sneaking across active railroad tracks, and then repeating the exercise on the

other side of the tracks to emerge to safety and avoid arrest for trespass

(John’s preferred option). Our

odometers said 102 miles, I was really hot, and I was not excited about adding

to our mileage total so I elected to push on through the construction area

despite the almost certain marital discord that this would create. At the first ditch I stuck my foot in sticky

mud up to the ankle, almost getting my shoe sucked off. Beth followed with a similar mucky

result. When we got back on our bikes, a

now decidedly unhappy Beth had too much mud in her cleats to clip in and had to

complete the last six miles “unclipped”.

Her bike was a muddy mess. As a result, I deservedly wound up in the dog

house and for penance had to spend the hour after we completed the ride

scrubbing the mud out of every mechanical orifice of our muddy bikes and shoes. Beth was nice enough to point out at the

finish that there was an easy bypass to this construction disaster that would

have only added five minutes to our journey.

I promised to listen better in the future.

Beth "enjoys" Another Bridge Out Adventure -Poplar Bluffs, Missouri

Mud in the Cleats - Poplar Bluffs, Missouri

Nebraska – “It’s Not for Everyone”

Tornado Watch

We pulled into Beatrice (Be-At-Riss), Nebraska after the

550-mile drive from southwest Missouri where we had completed our last

ride. The weather was sunny and pleasant

when we arrived and the setting would be good material for a Nebraska tourist

flyer, with a large well-appointed camper poised on the edge of a one-acre farm

pond with happy bullfrogs and peepers keeping things lively.

We settled into bed for what we thought was going to be a

peaceful night of sleep. We were

expecting some friendly thunderstorms at some point but none of the tornado

warnings that had been common during the last week in this area were

posted. At about midnight we woke up to

howling winds and nearly continuous flashes of lightning. The trailer was rocking in the wind and

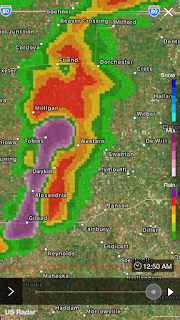

visions of us upside down in the adjacent pond flashed in our heads. A quick check of the radar on our phones

showed a thick band of angry reds and purples headed in our direction,

accompanied by tornado warnings with our present location in the

cross-hairs. Our host was urgently

texting us, and we retreated to the basement of her house and waited things out

for half an hour before returning to the camper for six more hours of sleep

punctuated by occasional rumbles, wind gusts, and pelting rain. When we woke up at 6:00 to the sound of more

thunder, wind, and rain we decided it was an excellent time to spend one of the

“contingency days” in our schedule to let our bodies and minds refresh

themselves. On our ride through Kansas

a few days later we went through the Town of Linn, where the elementary school

had been boarded up after a pummeling by a tornado. We had managed to keep our bikes out of the

violent weather to this point, but tornados are an ever-present discussion in

these parts, particularly during the record-setting year of 2019 when at least

eight tornados had touched down in the Midwest for 12 straight days during our

trip, including one day with over 30.

The View From John's Cell Phone Weather App in Nebraska (purple is bad)

Sketchy Protection from a Tornado - Beatrice, Nebraska

The start of our ride in Beatrice, Nebraska was made more

interesting when the nice police man told us that we ought not park where we

were thinking of parking in the town lot because there was a good chance the

Big Blue River would be out of its banks and up to our car doors by the time we

returned. We found a location on higher

ground and pulled the tandem out of the car for its maiden century voyage. Our route took us west from Beatrice to Fairbury,

a distance of about 30 miles. We faced a

strong headwind out of the west from the first pedal stroke, and by the time we

pulled into Fairbury we had made only a 13 mph average and were pretty beat

up. The route then headed south (with a

cross wind) and then back east. Once we

got the wind at our backs on the east-bound leg our lives improved

considerably. With our four legs pushing

on the pedals and a 20 mph tailwind we blasted the next 30 miles with our

speeds dropping below 25 mph only on the steeper uphill sections. In one segment on the return trip our time

ranked us at the top of the leader board of the 60 or so cyclists that have

completed this section and listed their time on the Strava application.

Homeward Bound with a Tailwind - near Odell, Nebraska

Our last stop of the day was in Odell, Nebraska at a little

store that is owned and operated by the members of the community. The cashier explained to us that because the

town is too small to support a privately-owned store, the members of the community bought a

building and operate the store as a co-operative, largely with volunteer labor. It’s apparently a common model in the small

towns of the Midwest. We finished our

Nebraska ride with a 15-mile push into a headwind, but all-in-all it wasn’t too

bad a day and we enjoyed our fastest average pace to date.

Kansas – It’s in the

middle

The Middle

Kansas went wrong from the start. We liked the Town of Odell, Nebraska the

previous day so much that we decided to drive 25 miles from our lodging spot to

Odell to begin the ride to Kansas. The Town of

Odell is located only about 5 miles north of the Kansas border, so we were able

to start there and head into Kansas so the ride would “count” as our Kansas

century. The governing regulations for

John and Beth’s century quest specify that only 50 miles of the state you are

claiming must be done in that state, as long as the total ride is 100 miles or

more. The day started with severe

weather alerts, so we delayed our normal 6:00 AM start time by about 90

minutes. When we pulled the tandem out

of the car in Odell we realized immediately that we had forgotten our water

bottles, which earned me a one hour round trip drive back to Beatrice to remedy

the situation.

A Tree and a Windmill - Kansas

When we finally rolled out at 9:00 the headwinds from the

west had returned with a vengeance for a second day. Our legs were not amused with this situation

since this was the first (and ultimately only) day of the trip where we had

scheduled back-to-back days with century rides.

We’d had some route-planning challenges, so this ride was an

out-and-back course that went south then west then east, then north on a single

numbered road. We knew, or thought we

knew, that every mile we pedaled into the wind would be re-paid with a tailwind

on the return trip, so we did not entirely mind the investment of energy we would be making on the out-bound trip. We started south

into a cross-wind that was mostly in our faces for about 15 miles. Now in Kansas, we turned west straight into

the teeth of it and had the same miserable 13 mph experience we’d had the day

before in Nebraska for another 30 miles or so.

As we neared our turnaround point I noticed that the wind was shifting

from a west wind to a north wind, such that as we rolled home we did not get

much benefit from the wind going east and then got it right in our face again

going north. Added to that were a series

of long rolling hills that we had not expected.

And the worst insult of all was that the little community restaurant

that we had been counting on for a piece of apple pie at 75 miles had closed

before we got there. I don’t want to

talk about this ride any more – we both ultimately voted this as the worst ride

of the trip.

Finishing Kansas and Back to Nebraska - Not our Favorite Day!

Week 3 – Oklahoma, New Mexico

Oklahoma is OK

We took an entire day to drive from Nebraska to Oklahoma

(another 550 miles) and decided early in the day that we’d take the next day

off to allow our bodies to recover from the physical insult of back-to-back

tandem rides in winds of Nebraska and Kansas.

Along the way we stopped at a Pawnee Indian Museum and then again at the

exact geographic center of the lower 48 states, which is in north-central

Kansas. How someone mathematically

figured out the location of the center of the U.S. we may never know, but it’s

essentially the location where you could balance the U.S. on your finger if you

had a perfect cut-out model (which I assume no one has).

Our jump off point for the Oklahoma Century was Boise City,

Oklahoma, which is in the western part of the Oklahoma pan-handle and

interestingly (at least to me) within 30 or so miles of four different states

(KS, CO, NM, TX). We had originally

planned to do a circuit that would hit the state borders of both Kansas and

Texas, but once we got to Boise City the locals suggested we go the opposite

direction, so we planned a ride west to Black Mesa recreation area in the

extreme northwest corner of the State on a route that would take us to the

borders with both New Mexico and Colorado.

Our day off in Oklahoma started with a pancake breakfast

hosted by the local rotary, followed by a quilt show (very impressive!), and

then a test drive (in the car) of the route we were to ride the following

day. Along the way we stopped in the

town of Kenton, Oklahoma, very close to the New Mexico border. We visited with a lively couple who married

71 years ago and ran the history museum in town. They showed us the barbed wire collection

with great (and well deserved) pride. The proprietor (Fannie) told us that she

had been born 90 years ago in the very building we were standing in. Her family never owned the building but when

another family moved out in 1929 her family simply moved in, an acceptable

practice in the struggling community. Fannie

was one of 30 students in a thriving elementary school in the 30s. Today there

are no children, no businesses, and very little way to make any income since

even agriculture is tough in the dry western part of Oklahoma. The closest town is over 30 miles away. It wouldn’t surprise either of us to come

back in 10 years to find a ghost town here.

When we returned to our temporary home in Boise City, the

town was having its annual “Santa Fe Days”, which featured POST HOLE DIGGING,

wherein they line up a bunch of Sooners, give them post hole diggers, and then

provide them with three minutes to dig as deep as possible (31 inches won

it).

Sturdy Oklahoma Farm Girls at the Post-Hole Digging Contest - Boise City, Oklahoma

The first two weeks of our trip has been a cycling

whirlwind, with seven 100-mile rides completed between Ohio and New Mexico in

14 days. The pace of our journey will

now slow down a bit as we move into the part of the country where we’ve got

contacts and an increased interest in lingering.

After reading the account of our first two weeks of riding

and driving on our cycling quest across America, my mother remarked “It all

seems to be pretty miserable to me. You

don’t seem to be having a good time”.

She clearly does not understand the importance that suffering plays in

personal fulfillment. Plus, it’d be a

really boring trip if everything went well so we will continue to celebrate

both the highs and lows of our adventure.

Just two rides were completed during the third week of our

trip:

Start Point

|

Date

(2019)

|

Riding

Distance (miles)

|

Elevation

Gain (ft)

|

Average

Speed (mph)

|

Max

Speed (mph)

|

High

Temp

|

State

Century

|

Boise City, OK

|

6/2

|

101

|

3182

|

16.0 (tandem)

|

40.2

|

75

|

#40

|

Taos, NM

|

6/6

|

101

|

6410

|

13.5

|

49.3

|

75

|

#41

|

Oklahoma is OK

Our rest day in Boise City, Oklahoma had returned a little

zip to our legs for our 100-mile out-and-back Oklahoma tandem ride in clear

weather conditions. The western portion

of Oklahoma is often described as the spot where the plains meet the foothills

of the Rockies. For the first 25 miles

of our ride we were definitely in the plains with a straight road heading out

of town to the west through unbroken ranchland.

This was the most isolated country we’d been in so far, with very little

in the way of improvements of any kind.

Our 6:00 AM start meant we were free of the winds that had plagued us in

Kansas and Nebraska and we made good time to our first water stop at Black Mesa

State Park at the 25 mile mark. Our

out-and-back route featured three excursions off of the primary route to boost

the mileage to 100 – the first was north from the Town of Kenton to the

Colorado State Line, the second was to the west to touch the New Mexico state

line, and the third was to the south to make up for a mileage miscalculation

that would have brought us in too soon.

An Empty Road on Oklahoma's Panhandle - Two Cars Passed us in the First 40 miles

Taking a Break near Kenton, Oklahoma

In Kenton we stopped again at the Historical Society to fill

our water bottles and meet some more with Fannie, the 90-year old lifetime

Kenton resident that we’d met the previous day.

She filled in some more details about her childhood in this little

struggling town, including a description of her 3-mile commute to Town from the

family’s ranch, which she completed each school day starting at the age of 9

with her 14 year old sister aboard the family’s aging horse. Once at school they’d put the horse in the

corral out back for the day and return home at the end of the school day by the

same means. She explained that when the

weather was too difficult to return home that she and her sister would have to

find lodging in Town with another family or at the local hotel. It was a Town and a time where folks looked

out for each other and life’s lessons came early. As Beth shared stories with Fannie I quietly

ate my lunch at a nearby picnic table, enjoying a large bag of nut mix and M and Ms that I mistakenly assumed Beth had prepared just for me, a selfish act

that I would later regret.

Beth with the 90-year old director of the Kenton, Oklahoma History Museum

(scene of the nut mix debacle)

The middle section of our ride on this day was through the

high mesas of extreme western Oklahoma, including Black Mesa, which rises about

1000 feet above the surrounding topography and is the highest point in

Oklahoma, at 4977 feet. There were

several steep climbs in this section which gave us the opportunity to use the

lowest gears our triple chainring tandem.

We spotted several Pronghorn Antelope along the road, including one that

paced alongside us was we cruised down the road at about 20 mph.

Where the Plains End and the Rockies Begin - near Kenton, Oklahoma

The steep uphills in mesa country were tough but expected

and we climbed them with only a modest amount of suffering in our super-low

tandem hill climb suffer gear. The

misery came later when the tailwind we were expecting to have the entire return

trip turned out to be a strong headwind from the south for about 15 miles

starting at the 75 mile mark. At the

lowest of the lowpoints heading into the wind Beth remarked “I need to stop

right now. My feet hurt, my butt hurts,

I’m about to cry, and I’m really mad at you for eating all the nut mix (which I

had)”. Beth was suffering from an

affliction well known to cyclists as “bonking”, a condition exacerbated by her

lack of nut mix nutrition. After a few

minutes sitting at the side of the road with her shoes off reviving her feet

and ingesting some non-nut mix foodstuffs, Beth was restored and we turned

around for the final 25 miles into Town, which was covered in about an hour now

that the wind was at our back. Beth’s

faith in the joy of cycling returned and her husband was mostly forgiven for

eating all the nut mix, although I’m sure penance will need to be paid at some

unexpected point in the future.

Camping Adventures in Oklahoma

We had an extra contingency day programmed into our schedule

after our Oklahoma ride so at the end of our ride we headed out to a campground

near Black Mesa. Our goal was to stay

two nights and do an 8-mile hike up Black Mesa on the off day.

The weather pattern that had developed over the previous

week in the western plains was clear sunny mornings followed by a bunch of wind

in the afternoon and thunderstorms or the risk of thunderstorms in the late

afternoon. When we pulled into Black

Mesa State Park at about 5:00 after our ride there was an angry black

thunderstorm gathering itself for a big punch.

We quickly set up our tent and managed to cook dinner and clean up

before the rain got started at about 7:00.

Over the next two hours the storm raged around us, growing in intensity

as we lay hunkered down in our tent. At

the height of the storm, the rain (and then hail) was coming down impossibly

hard and there was a nearly continuous roar of heavy thunder overhead, more

than I’d ever heard. Our flimsy Eureka

Timberline tent was getting badly buffeted by the wind and we thought there was

a pretty good chance that it would collapse around us and leave us a sodden

mess. Eventually the winds abated, the

hail melted, and our tent survived to house us another night. We were only slightly sodden.

We emerged from our wet tent the next morning to bright

sunshine and hiked to the top of Black Mesa, a trek of four miles each

way. The mesa is comprised of resistant

volcanic basalt (same stuff they used to build Hawaii). It’s located as far north and as far west as

you can get in the Oklahoma panhandle.

For you trivia buffs, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, where the mesa is

located at the western tip of the Oklahoma panhandle, is the only county in the

United States that borders four states (TX, NM, CO, KS). There were great views from the top and a big

granite monument that was transported up there by some mysterious means. Wildlife sitings on the walk included a horned

toad, a species I’d not seen previously.

Hike to Black Mesa, near Kenton, Oklahoma

Beth atop Black Mesa, Oklahoma's Highest Spot (4977 feet)

The dark storm clouds started forming again at about 3:00 PM

that day after we got back to our campground and by 3:30 it was starting to

blow pretty hard. We battened down the

tent and went for a little walk before the inevitable rain blew in. As we passed the ranger’s residence, we heard

a crack and watched as a large tree limb fell across a powerline. The powerline arced with a bright flash and a

tree limb caught fire for a few seconds.

We alerted the nice ranger lady who explained that power had been lost

and that there was no longer water available to flush the toilets in the

campground, a sanitary inconvenience that seemed somewhat problematic to us.

A Bad Day for Tent Camping - Black Mesa State Park, Oklahoma

We returned to our campsite after speaking with the ranger,

and found that the wind had snapped a tent pole and created other mayhem to our

residence. The poles had pulled away

from their anchors, and the wind was trying hard to launch our lodging into oblivion,

which was being prevented only by the weight of our belongings in the tent. We managed to splint the broken pole with

another pole and some duct tape, but then the wind speed moved to another

(higher) level and we found ourselves standing in lightning and spitting rain

holding on to both ends of the tent to keep it from being damaged further or blowing

away. After about 10 minutes of this we

decided it was hopeless so we pulled out the poles and stakes and rolled up the

tent and its contents, sleeping bags, pads, and all and stuffed them into the

van in favor of more comfortable sleeping accommodations, which we found about

45 minutes later, along with another sodden family from the campground, at the

Super 8 Motel in Clayton, NM.

Rainbow Spotted during our Harried Retreat to New Mexico

New Mexico – The Enchanted Circle

The jump-off spot for our New Mexico ride was in Taos, where

we’d rented a great place on AirBNB. To

kill some time before check-in we stopped at the local bike store to ask some

folks in the know about the route we had planned, which made use of the iconic 85-mile

“Enchanted Circle” route that circumnavigates New Mexico’s highest point, Mount

Wheeler (13,000 feet and change).

“No. Under no circumstances

should you do that route” explained the woman behind the counter. “The ride up Taos Canyon is twisty with no

shoulder and a lot of traffic”. She gave

us an alternative route which was less appealing to us. We then moved on to the

next bike store to get their opinion on the Enchanted Circle ride.

“It’s a great ride, you should definitely do it”, said the owner. “Just get an early start and you’ll be

fine”. We liked the second opinion

better but heeded the first store’s warning about traffic and decided to get an

early start and reverse the direction I’d originally proposed so we could go

over Taos Pass as early in the day as possible.

Beth has not historically been an early riser, and does not typically

relish rising while the sun is still on the other side of our planet; however,

in rare cases, primarily when she is motivated by fear, she is willing to make

an exception. The morning of June 6,

2019 was one of those exceptions, her fear driven by a triad of time-sensitive

hardships that included traffic, heat, and headwinds.

We rose that morning at 4:30 AM and rolled out a few minutes

before the sun rose at 6:00. The

temperature on my Garmin bike computer was 41 degrees as we headed east up Taos

Canyon toward our first pass, which was 18 miles away. The sun didn’t find its way into the canyon

for over an hour, and the temperature dipped as low as 34 degrees as we headed

up the canyon road. The climb to Taos

Pass at 9300 feet was relatively gentle and our cold fingers and toes didn’t

mind a little physical activity. We made

it to the top feeling good, and from the top it was a fun-filled twisty 1500

foot drop into the Town of Angel Fire, where we stopped to fill water bottles

and grab some eats. From there we headed

north up the east side of the range with great views of a snowy Mount

Wheeler. The route took us through Red

River and then turned upward toward Bobcat Pass, which at 9970 feet was the

high point of the day. This was a long

climb which got steeper as we went, a good test our fitness and our ability to

work hard at altitude. We passed the

test and then enjoyed a long downhill to the town of Questa at 75 miles.

Top of Bobcat Pass on the Enchanted Circle from Taos, New Mexico

Beth on the Climb to Bobcat Pass, near Taos, New Mexico

Since we were still nearly 1000 feet above

Taos and the wind was blowing in the direction we’d be headed, we thought it

would be an easy run into town.

Unfortunately, as we have been finding out nearly every day, the last 25

miles of these rides is rarely easy all the way. “You’ve got a bunch of big hills coming as

you ride south out of town” said the woman at the Questa Visitor Center when

Beth asked about the road. She was not

exaggerating. They were big and there

were a bunch. On the flip side, we were

rewarded with some fast downhills (49+ mph) and there was indeed a tailwind

helping us along. We had an uneventful

ride through the busy streets in Taos, and finished this one at 101 miles with

big smiles on our faces.

Week 4 – Wyoming, Montana, Washington

From New Mexico we drove to Evergreen, Colorado where we

spent a couple of wonderful days with our college friends Fred and Marggi

Seymour. We did some hikes with Fred and

Marggi and enjoyed spending some well-deserved rest time before our next

push toward the northern Rockies.

Start Point

|

Date

(2019)

|

Riding

Distance (miles)

|

Elevation

Gain (ft)

|

Average

Speed (mph)

|

Max

Speed (mph)

|

High

Temp

|

State

Century

|

Laramie, Wyoming

|

6/11

|

100

|

5459

|

15.6

|

49.2

|

70

|

#42

|

West Glacier, MT

|

6/15

|

100

|

6909

|

14.3

|

35.7

|

70

|

#43

|

Spokane, WA

|

6/17

|

102

|

5331

|

14.4

|

49.9

|

80

|

#44

|

Wyoming – Cheating the System - Snowy Pass, Medicine Bow Mtns.

We stayed in Laramie with our friend Evan Johnson and his

wife Fawn. Evan had lived in Willimantic

while he was a graduate student at UConn and he’d joined us on previous running

and cycling adventures in the Nutmeg State.

He’s now professor in exercise physiology at the University of Wyoming

and is looking forward with Fawn to becoming a parent in the fall.

Knowing that Evan is a super-fit 37-year old, we had

suggested a few months ago that he plan us an epic 100-miler that made use of

Wyoming’s mountainous landscape. His required participation in this epic 100-miler was not negotiable. Evan seemed a little trepidatious about

riding 100 miles, particularly of the possibility of getting his butt kicked by

woman old enough to be his mother, but Evan is a good sport and always up for

an adventure, so he relented and charted us a route over Snowy Pass in the

Medicine Bow Mountains west of Laramie.

To keep things interesting, Evan had planned a point-to-point route on

Wyoming Route 130 from Walcott to Laramie that required a 100-mile shuttle of

the three of us and our bikes over Snowy Pass and out into the plains on the

other side.

When I looked at Evan’s west-to-east one-way route, which

involved a 3500-foot vertical climb to the top of Snowy Pass from his proposed

start point in Walcott, WY, I began to concoct a devious plan. “How’s about we have your friend drive us 50

miles out to the top of the pass. We’ll

then start our ride with a 25 mile downhill going west, turn around and climb

the pass once going east with the legendary Rocky Mountain easterly wind at our

backs, and then cruise the last 50 miles from the top. That way we’ll get to

drop twice as far as we climb and have a tailwind for our last 75 miles”. Evan didn’t have to be asked twice as this

meant he only had to keep up with the 59-year old mother of two for one major

climb and not two. Beth was asked

whether this approach violated any of the provisions of her 50-state century

quest guidelines. After consulting with

the rest of the governing committee, which was limited to her husband, Beth and

the committee determined that a net 3500-foot drop and a 75-mile finishing

stretch with a tailwind would be just fine.

With our Friend Evan Johnson Boarding the 6:15 AM Shuttle, Laramie, Wyoming

Afternoon thunderstorms are an almost daily occurrence in

the Rockies this time of year, so we woke up early and hopped on the one-way

shuttle provided by Evan’s friend Jason to the top of the pass at 6:15 AM. By 7:30 we were standing with our bikes in a

very snowy parking lot at 10,600 feet with the soaring peaks of the Medicine

Bow Mountains before us. The road crews

had finished clearing the snow from the pass only a week before, and high snow

banks on either side of the road added to the dramatic effect. Since we were starting at the top and would

be coasting downward 3500 vertical feet in sub-40-degree temperatures, we were

bundled up pretty well. We dashed down

the hill with the hopes of getting into warmer weather, and eventually our

prayers were answered as we descended out of the snow and into the dry

plains. The winds from the west were

picking up as we approached our initial turnaround at 25 miles near Walcott,

which was fine with us because we were about to get those winds at our backs

for the remainder of the ride. We

stuffed a bunch of clothes in the back rack I had installed on my Cannondale

for this occasion and started our 3500-foot climb back to the pass. We made it over the pass in fine form, with

Evan keeping up with the two elders quite admirably, although he did spend some

time whining about knee pain. His older

arthritic colleagues suggested he get used to it as he had about another 50

years to go before he found relief from joint pain (if you know what I

mean). He informed us at the 45-mile

mark that he had already logged more miles that day than he’d logged any single

day in the last five years. We then felt

bad about his knees and our dismissive comments.

Launching our Wyoming Ride - Snowy Pass, Medicine Bow Mountains (34 degrees!)

Ready for a Chilly 3500' Descent from 10,600 feet

Medicine Bow Mountains, west of Laramie, Wyoming

Beth and Evan Cresting Snowy Pass on the Return Trip, Wyoming

We stopped in the Town of Centennial at 65 miles for lunch

after a screaming 3000+ foot drop from the top of the pass. After that we were onto the open plains with

strong tailwinds that rocketed us back to Laramie often seeing 30 mph on the

flat roads. The 16.0 mph that was on our

odometers as we rolled into town was the fastest average we’d experienced on

the trip on single bikes. A tailwind and

3500-foot net descent will do that.

Montana – To the Sun and Back (Twice)

From Laramie we drove northwest to Jackson, Wyoming, which

surpasses Taos as a destination for the rich and famous. I provided Beth with some fiery entertainment

at dinner by accidentally ingesting the majority of a large habanero pepper

before realizing that this item on my plate was not intended for human consumption

and was definitely not the mild yellow pepper of the Big Y variety that I

expected.

Teton Mountains, Jackson Hole, Wyoming

We passed on the pricey Jackson hotels in Town and camped in

the Gros Ventre National Park Service campground outside of Town. At the campground we had an interesting chat

with a weathered Australian guy who was taking an evening break on a motorcycle

trip that had originated in Panama. He’d

passed through all of the Central American countries where most gringos fear to

go. While negotiating Nicaragua he encountered an informal road block that had

been set up by some local residents to separate motorists from their cash. The machete wielding attendant asked him for

the equivalent of 30 dollars. “I’m not giving you $30”, he said, “How about

$3”. “Sounds good”, said the man with

the machete, who then took the cash and happily sent him on his way.

From the Tetons we followed a line of Winnebagos on to Yellowstone

for a little sightseeing. We had to

deflect from our original plan of driving past Old Faithful because VP Mike

Pence and the Secretary of Interior were visiting the park that day to tell the

world how much President Trump loves nature.

We were impressed at the lengths to which the present administration is

willing to go to personally annoy us, Mr. Pence’s visit being only the latest

example. Our alternative trip up the

east side of the park featured sightings of hot springs, grizzlies, black bears,

and bison, as well as a hike along the rim of the Grand Canyon of the

Yellowstone River.

Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Wyoming

With all the Yellowstone campgrounds full, we continued into

Montana and spent a night in the mining town of Butte, where they’ve pulled 53

billion dollars’ worth of copper out of the ground over the years and have

built a museum to commemorate the 2300 miners that have met their maker during

that process. Then we were on to

Whitefish, Montana, the jumping off spot for our ride at Glacier Park, which

would be State Century #43.

We stayed in Whitefish with one of my college roommates,

Jeff Mow, and his wife Amy. As luck

would have it, Jeff is the Superintendant for Glacier Park, and someone who was

intimately familiar with the area. Jeff

had informed me a few months earlier that the iconic mountain road through the

park, the Going to the Sun Road, would be open only to bicycles for the weekend

prior to the official opening of the road on June 22, as long as snow clearing

had been completed by that date. This

was not a snowy year in Montana, and they had completed the snow clearing about

a week before we got there.

The road stretches 50 miles from the western entrance gate

to St. Mary’s on the east and climbs 3500 feet up to Logan Pass at an elevation

of about 6600 feet. While this is not

particularly high from a Rocky Mountain standpoint, it’s an extremely snowy and

alpine setting due to its latitude, which is only 30 or 40 miles south of the

Canadian border. There’s one spot where

it’s not unusual for the road crews to have to clear a drift that’s 90 feet

high to get the road open.

It’s about a 25-mile ride up to Logan Pass from the western

entrance, which created an issue for us because a ride to the top and back

would only give us half of the 100-mile distance we needed for our quest. Our solution was to ride up to the top and

then down the other side to the Town of St. Mary’s, which was a perfect 50

miles one way from the western entrance.

Once in St. Mary’s, there was the small issue of re-scaling the 3000 vertical

feet back to Logan Pass, but I assured Beth that the nine century rides she’d

already completed in the past four weeks and her altitude training made her

well suited to the task. I didn’t really

know this, but it sounded good at the time.

Our departure up the mountain was delayed by 30 minutes

because the alarm on my watch was effectively sound-proofed by a pillow that

resided on my wrist. By the time we

finally got to our jump-off spot at the eastern entrance at about 7:00 there

was already a stream of cars with bikes headed to the section of road which is

closed to motor vehicles. The first part

of the ride, along Lake Macdonald, was open to vehicles, but when we got about

15 miles from the entrance there was a gate across the road at the Avalanche

campsite. The vehicles were parking and

disgorging hundreds of cyclists eager for the once a year chance to ride the

road without fear of being pushed over a cliff by a lumbering motorhome.

The 3500 vertical foot climb to the top of Logan Pass is big

challenge, and we assumed that participation in this event would be limited to

those on 16-pound carbon race bikes powered by 25-year old legs. In this assumption we were incorrect. There was every type and style of bike

imaginable. We saw 12-year olds, we saw

80-year olds, and we saw people carrying their dogs in baskets. In this part of the world, the bike ride up

Glacier before the road opens to cars is a community celebration, and everyone

wants a part of it.

Random Woman and Her Dog - Logan Pass, Going to the Sun Road, Glacier Park, Montana

About 10 miles from the top of the pass the grade kicks up

and you start the serious climb. The

engineering that went into this road, which was built in the 1930s using

Civilian Conservation Corps labor, is remarkable. It’s literally hacked into the side of a

cliff, and an excursion off the side of the road would reward you with a

downward flight of several hundred feet before you hit something solid. Between you and that downward flight there’s

typically an eighteen-inch high stone wall, which would give you a nice launch

off your bike if you ever had the misfortune of encountering it. The views are so spectacular it’s hard to

believe they’re even real, with sheer cliff faces punctuated by snowfields and

towering waterfalls for the upper portions of the climb.

Beth Climbing Logan Pass from the West - Glacier National Park, Montana

Climbing Logan Pass from the East Side (St. Mary's) - Glacier Park, Montana

Beth Riding Through The Big Drift East of Logan Pass, Glacier Park, Montana

Snow can be as deep as 90 feet at this location in the Spring

Grades on the climb were a steady five to seven percent,

pretty gradual by our eastern Connecticut standards, and as we pushed on up the

hill, we realized that we weren’t even needing our lowest gears. At one point, while I was feeling quite full

of myself for my climbing prowess, I heard a buzzing of knobby tires coming

from behind me at a solid pace. A young

woman then passed me on a fat bike. This

was remarkable to me not because she was a woman (I’ve gotten very used to

being passed by women) but by the fact that she had a child on a bike seat

behind her and she was towing a second child in a trailer. I quickly estimated the weight of her rig –

120 pounds for her, 40 pounds for her kids, 40 pounds for her bike, and another

30 pounds for the trailer and rack, for a total approaching 250 pounds. A short time later her husband pedaled up

next to me, “You don’t need to feel too bad”, he said, “it’s got a battery

assist feature. I saw you looking over at them and thought you ought to know”. Whew.

Beth and I made it to the top in good shape, and joined a

few dozen other riders for our selfies in front of the Logan Pass sign. We then did something we saw nearly no one

else doing, we went over the top and down the other side. By that time the top of the pass was in a

cloud, and the 44-degree wet air made for a distinctly chilly descent. The highlight of our ride down to St. Mary on

the east side was the sighting of a bear grazing in some shrubs on the side of

the road with her cub perched in a nearby tree.

Jeff had informed us that the Glacier region is home to approximately

1000 Grizzly Bears, the highest concentration of Grizzlies on the planet. With that many Grizzlies, encounters with

humans are inevitable, and Jeff had given me a large container of bear spray

which I had in my Camelback, “just in case”.

Our encounter with the bear on the side of the road did not constitute

such a case, so thankfully the bear spray remained in its container. I did talk to a guy on the way up who

admitted he’d accidentally sprayed himself I the face with his bear spray twice

this spring, something he suggested we try to avoid.

After a quick bite at the bottom in St. Mary’s we did a 180

and started the climb back up the hill.

As we climbed back into the snow from the east, we noted some dark storm

clouds gathering to the west, but with our car on the west side of the

mountains we didn’t have a lot of alternatives for getting back. Just as we went over the top of the pass, we

felt the first rain drops. Then a lot of

additional rain drops, and then a deluge as we descended. Many of the riders who had started down were

now hunkered under overhanging cliffs trying to get out of the rain. We elected to keep dropping in an attempt to

get to some warmer temperatures.

Remarkably, the riders that were heading up the hill just kept coming

despite the deteriorating weather. Many

of them were wearing cotton t-shirts and no jackets and we wondered about how

the rest of their day was going to go. Once down to the bottom of the mountain

the sun returned, and we enjoyed a flat 20-mile ride back along Lake MacDonald

with a tailwind.

The rides over the snowy passes in Wyoming and Montana were

the most exhilarating and rewarding of our trip and both of us ranked them at

the top of the list.

Washington – it’s on the left side of the map

We said goodbye to our hosts Jeff and Amy in Whitefish the

next morning and pointed the bug-splattered deer-damaged warning-light-flashing

Dodge Caravan without a back door west toward Washington. Along the way we stopped in Wallace, Idaho,

and decided we’d return there in a few days for Century #45. Upon arriving at our next destination in

Spokane, we found the campground we’d selected was full, so we selected option

2, a cheap motel on the outskirts of town.

We went to bed early for an early morning start.

“Who is this woman and what has she done with my

not-a-morning-person wife?” were my first thoughts when someone purporting to

be Beth woke me up at 4:00 AM to get ready for our Washington ride. The weather forecast was for temperatures in

the high 80s and Beth was looking to avoid riding in the heat, resulting in the

pre-dawn mobilization. (Note from Beth: I have not changed my watch from

eastern time, so according to my watch, it was a reasonable 7:00 am.)

I had originally mapped out a route about an hour drive

north of Spokane, but we were both getting sick of driving, so Beth googled

“Century Rides Spokane” and we were able to get a map for the “Lilac Ride”, an

organized 100-miler that had gone out of Spokane a month earlier. We went to the advertised start location of

the ride at Spokane Falls Community College and were greeted by scary “Permit

Only” parking signs. We went next door

to the Unitarian Church where there were more scary signs indicating that we’d

be towed if we even thought of parking there.

We parked there anyway, and Beth put a note on the dashboard saying

“We’re Unitarians from Connecticut that are parked here to do a bike ride. We’ll be back to the car by 3:30 and will

remove our car at that time. Please

don’t tow us”. And with that, we locked

up the van with our valuables inside and were off on our two-wheeled Washington

adventure wondering along the way if the Unitarians of the Spokane variety

would believe our sign and take pity on us.

The Washington ride started with a wonderful 10-mile section

on the Centennial Trail along the Spokane River, which tumbles through a canyon

at the edge of town. After about 10

miles along a relatively busy State highway the road headed into the less

populated countryside of eastern Washington via Corkscrew Canyon Road, which

lived up to its scenic moniker. Beth and

I loved the countryside of eastern Washington, which was rolling and

varied. At a little over 50 miles we

reached the turnaround spot of our ride in the Town of Reardon, which was the

furthest west we’d reach on the trip before heading back east. We celebrated with a couple of selfies in

front of their mule-themed municipal décor, and ate some breakfast burritos at

the local diner.

Our Furthest West Point on the 2019 Trip - Reardon, Washington

Seventy Miles Down, Thirty to Go - West of Spokane

Canola in the Sunshine - Washington State

Beth Rolls Through the Undulating Terrain of Eastern Washington

On our way back to Spokane we spotted some cyclists on the

side of the road and stopped to talk.

They were from a loosely organized cycling group in Seattle called

“Goosebumps” and were on their annual club excursion. “We’ll be having a happy hour in Room 209 at

the Hampton Inn at the Airport if you’d like to come join us after your ride”,

they said. “We just might”, we

said. A few hours later, after we’d had

a good conclusion to our 100-miler back to our untowed car, we found ourselves

at Room 209 in the Hampton Inn with a group of 15 or so folks that seemed a lot

like us. Stories were told, beer was

consumed, and we went on to have a wonderful dinner with this group, which we

had no doubt we’d belong to if we lived in the top left corner of the U.S.

map. Our chance encounter with the

Goosebumps club and the good time we had with them was just the latest example

to us of how important it is on a trip like this to allow your plans to be

fluid and to embrace the challenges, unforeseen situations, and chance

encounters that arise along the way.

Week 5 – Idaho

Start Point

|

Date

(2019)

|

Riding

Distance (miles)

|

Elevation

Gain (ft)

|

Average

Speed (mph)

|

Max

Speed (mph)

|

High

Temp

|

State

Century

|

Wallace, Idaho

|

6/19

|

103

|

1742

|

15.4

|

24.4

|

60

|

#45

|

Idaho – Century Prelude on the Hiawatha Trail

Our fist ride got off to a rough start. The Hiawatha Rail Trail on the Montana side

of the Montana/Idaho border near Interstate 90 makes use of the last

transcontinental railroad line to be built in the U.S. (1908) and over its

14-mile length features a dozen tunnels and another dozen or so high trestles

as it tries to maintain a grade of less than 2 percent as it passes over and through the Bitterroot

Mountains. The trail is operated as a

concession and the start is actually about 10 miles from where you buy your $15

ticket for the experience. Our research

on the trail was not comprehensive, and we had assumed that the trail was paved

in the same manner as most of the other rail trails we’d seen in the area. “Oh yes, the trail is completely paved and

you should have no problem” said the young woman at the reservation desk, who

had worked there a total of two days.

With confirmation that the trail was paved, we rented

the necessary clip-on lights to negotiate the tunnels. I was surprised that the lights we were given

were both covered with a layer of fine-grained light brown mud. I’ve done a lot of riding on Connecticut’s

gravel rail trails, and a trail has got to be pretty darn muddy to coat

something mounted on the handle bars with mud.

“Is the trail muddy?” I asked the freshly minted woman behind the desk. “It’s a little muddy in the first tunnel, but

you’ll be fine” she said. I wasn’t sure

how a paved rail trail could be muddy, but I trustingly took the lights and we

drove the 10 miles to the trailhead with our shiny road bikes in the back of

the car. When we arrived at the entrance

to the trail, known as the East Portal, we observed a gravel path emerging from

a tunnel in the mountain. There was not

a road bike in sight and the bikes and bodies emerging from the tunnel were

embellished with an impressive layer of pasty mud. “Is the trail paved?”, I asked the guy taking

tickets. “Oh no, what would have given

you that idea?” he said. “It’s a gravel

trail, the first tunnel is really wet, and you’re going to get muddy. Are you sure you want to ride those shiny

bikes with those skinny tires?”

Beth Enters a 1.7 Mile Long Railroad Tunnel

Hiawatha Trail, Bitterroot Mountains, Western Montana

We ended up renting a couple of rusty comfort bikes from the

guy, which required an annoying 20-mile car trip back to the spot where they

sell the tickets. Once that was worked

out, we were ready to go. The initial

tunnel at the start of the trail is the longest of the route and extends 1.7

miles. It was a slight down-grade in the

direction we were going. With tunnel temperatures

in the mid 40s and water dripping off the ceiling there was a distinct

chilliness to the start of the ride, so we did what most cyclist do when

they’re cold - we pushed the pace to generate some body heat. The wet trail, our knobby tires, and our need

for speed resulted in dual rooster tails of mud splattering pretty much every

square inch of our bodies by the time we exited the tunnel, particularly our

backsides where we could feel the layer of wet mud seeping through our lycra

and into the various epidermal nooks and crannies that reside beneath that

lycra.

Mud Embellishment on the Hiawatha Trail

With dampened bodies but undampened spirits, we continued

on, delighting in the fact that our shiny bikes remained locked in the

car. The balance of the 14-mile route

was the most spectacular trail I’ve ever ridden on with two wheels. The trail clung to the side of steep valley

walls with an average of about one high trestle and one tunnel every mile. Interpretive signs every half mile or so were

interesting and informative. This trail

needs to be on everyone’s life list, particularly if you can arrange to ride

someone else’s bike!

View of a High Trestle that Awaits Us - Hiawatha Trail, Western Montana

Beth about to Enter Another Tunnel on the Hiawatha Trail

Hiawatha Trail - Western Montana

Hiawatha Trail - Western Montana

We had planned to turn around at the western terminus and

ride the 14 miles back, but when we contemplated a 14-mile uphill return trip

on rusty “comfort bikes”, considered the fact that we’d be riding 100 miles the next

day, and saw everyone else happily loading their bikes onto a shuttle bus, we

decided that today was a good day to be wimps and we joined the throng for the

uphill return trip in the comfort of a school bus.

Idaho Century – Trail of the Cour d’Alenes

This one was supposed to be easy.

The Trail of the Cour d’Alenes is a 70-mile paved rail trail

that runs from Mullen to Plummer, Idaho in Idaho’s panhandle region just south

of Interstate 90. We hopped on the trail

near its eastern terminus in Wallace and pointed our bikes west, for a 100-mile

out and back. Like the Hiawatha Trail,

the Trail of the Cour d’Alenes is in the Rail to Trail Conservancy’s top 25

rail trails in the nation. The western

section of the trail passed through several mining towns including the town of

Smelterville where, you guessed it, they smelted the hell out of a mountain of

crushed rock to liberate its mineral wealth – primarily copper, zinc, lead, and

silver. The emissions from the

operation settled throughout the valley, resulting in ubiquitous soil

contamination in the area and one of the largest Superfund sites in the country. The paved rail trail and the gravel sub-base

beneath it protect users from the toxins in the soil and are part of the final

remedy the mining companies funded to pay for their past sins. Unless you knew this by reading the signs,

you’d pedal along on your merry way through Idaho’s beautiful countryside

oblivious to what’s under your tires.

Easy Outbound Roll on the Trail of the Cour d'Alenes, near Smelterville, Idaho

Trail of the Cour d'Alenes - Wallace, Idaho

We had a strong wind in our face on this ride right from the

start, but we didn’t mind it because we knew (or at least I knew) that we’d

have a tailwind of the same force for the last 50 miles and the forecast was

for clear weather all day. Beth was

unwilling to listen to my optimistic forecast, having been burned multiple

times on this trip in similar circumstances.

The sights got nicer as we went, with the trail running along rivers,

lakes, and large wetland areas. We

spotted lots of waterfowl and a bald eagle along the way as rewards for our

efforts. The habitat also seemed perfect

for the moose to round out our list of animals spotted along the way but we saw

none on the trip west. We were in high

spirits when we rolled into our turnaround location at the 50-mile mark in

Harrison. Lunch was at a restaurant

called One Shot Charlie’s where we each had a reuben sandwich and no

shots. Beth and I talked about the great

luck we were having with the weather and I again waxed on about the 25 mph

tailwind we’d enjoy on the return leg.

Sometime around the end of our lunch, Beth looked out the

window and realized that there were dark storm clouds gathering and coming our

way fast. We quickly paid the bill,

hopped on our bikes, and tore off down the trail with 50 miles ahead of

us. Neither of us had brought a raincoat

because the forecast that morning had been for ZERO percent chance of

precipitation. After about a mile Beth

said “Guess what, we didn’t remember to fill our water bottles”. With few options for water along the way, we

were forced to go back to the restaurant to get the bottles filled. Meanwhile, the clouds grew darker, and

closer.

Back on the trail again, we dashed eastward, with Beth in

the lead by a few hundred yards. She

suddenly stopped in front of me, pointing across a wetland. A cow moose had stepped out of the woods and

was feeding on some water lilies. Wanting